In 2008, we attended the Taller Internacional de Conservación y Restoración de Arquitectura de Tierra (the International Workshop on the Conservation and Restoration of Earthen Architecture). The following article about our experiences was published in The Last Straw Journal.

Looking for New Old Tools By Rebecca Tasker, co-owner, Simple Construct

The best builders I know are constantly looking for ways to improve or refine how they build and add to their tool kits (literally and figuratively). As a self-taught straw bale builder, information and inspiration come from far-flung and sometimes surprising sources. In this case, it was a week-long conference on the conservation and preservation of historic adobe structures that I attended with two colleagues in November 2008.

It might seem like the long way around the barn to apply the preservation of historic earthen structures to building contemporary straw bale buildings, but it’s an interesting journey and not really such a big barn.

The reason we straw bale builders were headed to this conference does require a bit of explaining. In 2005, the company I worked for, Distinctive Builders, built a 1200 square foot straw bale building called the Begole Archeological Research Center in the Anza Borrego State Park (about two hours east of San Diego). After completing the BARC, as it is known, we were invited to bid on building a protective structure over a turn-of-the-century earthen cabin that the park had recently acquired. We were the first contractors to show up to the job walk. We were also the only contractors to show up, which was not surprising given the logistics of the job: the site is three miles from the nearest potable water and more than a mile off the paved road down a soft, sandy track that was barely wide enough for a truck. But once we saw that little cabin, forlornly crumbling in the desert sun, we knew we wanted the job.

The cabin is less than 500 square feet, divided into two rooms. Remnants of pale cream plaster, blue trim paint, and a cloth-covered ceiling are visible. It was built from the local soil, wetted and packed between forms and poured or puddled in lifts. Part of one of the window bucks appears to be made of an old axe handle and an ingenious system of J-bolts and barbed wire were used to attach the top plate to the earthen wall.

Though the structure we built was simple—a post and beam shade structure which provides a new roof for the building without touching the existing structure—the remote, harsh landscape made building it an arduous process. This experience gave us a hearty respect for those brave and stubborn souls who reached the valley by wagon and decided to make it their home, building with whatever materials and skills were available to them.

After the completion of the protective structure, the park began to plan the stabilization of the cabin and we wanted to be involved. Knowing that there is a lot to know about earthen construction, my then-boss Alan Schmidt, my partner Mike Long, and I decided to attend a workshop on adobe preservation.

That is why we found ourselves heading to Southern Arizona and Sonora, Mexico for TICRAT AZ/SON. Taller Internacional de Conservación y Restoración de Arquitectura de Tierra translates as the International Workshop on the Conservation and Restoration of Earthen Architecture. It is a project of the Missions Initiative, whose purpose is to develop an international partnership for cultural resource management of the hundreds of Spanish Colonial Missions in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. It is co-sponsored by the National Park Service (NPS) and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH, the National Institute of Anthropology and History), with assistance from the Preservation Studies Program at the College of Architecture at the University of Arizona, and from Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a non-profit organization devoted to the preservation of architectural heritage and community traditions in the Southwest.

When we arrived in Tucson, we were met at the airport and told we needed to wait for one more of the group, a guy named Pat Taylor. To pass the time, Alan pulled out a book we had just bought on adobe conservation and noticed that one of the authors was a guy named Pat Taylor! This set the tone for the week: being pleasantly surprised by the caliber of the presenters and the relevance of the information presented. As we met other members of the group of about 40 people, it became clear that this was a well-informed and interesting bunch of people. There were superintendants and staff of various national parks; architects from both sides of the border and both neighboring states; and faculty and staff from the University of Arizona. There were also three Afghani cultural heritage specialists with the Ministry of Information and Culture who were able to join us for part of the week through a concurrent NPS program.

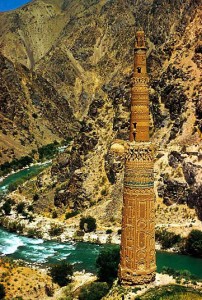

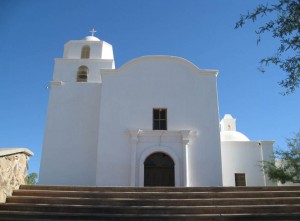

We heard lectures and case studies, each thoroughly translated between English and Spanish. We visited sparkling white iconic missions such as San Xavier Del Bac and crumbly brown, yet-equally-iconic missions like Tumacácori. Some had been restored as active churches such as Pitiquito, others as historic monuments such as Caborca, and others still were precariously and painstakingly preserved in a state of ruin. We heard lively debates about how to decide whether to restore, preserve, or let a ruin go. We saw pictures of an 800 year-old, 200-foot-tall Afghani earthen minaret. We got our hands dirty making adobe blocks and observed the lively process of slaking quicklime. We mixed and tested lime plasters, though it would be a stretch to say we helped in any actual preservation. Most importantly, we got to talk among ourselves at meals and between events and lectures, sharing our experiences and perspectives.

We had come to the conference to learn about preserving ‘our’ little earthen cabin but were also interested in exploring the distinct differences and broad overlap between adobe and straw bale construction. We learned that where straw bale is a system of super-insulation, adobe is one of thermal mass. The key to getting thermal performance from adobe is a combination of passive solar design and appropriate thickness. Studies done at the University of Arizona concluded that heat moves through adobe at about one inch per hour, so a twelve-inch-thick wall allows the midday heat to radiate at midnight and the cool of night to linger through the day.

Both systems utilize abundant natural resources with relatively low embodied energy. Water is the enemy of both adobe and straw bale walls and must be well managed. Both systems are “living buildings” that need to breathe (or, transpire). Because of this, it is in the types of plasters that the two systems are the most similar: clay and lime. The vocabulary terms were reassuringly familiar (sharp sand, shake tests, slaking, and carbonation) and it was a treat to see the ubiquitous Lime Cycle diagram presented in Spanish.

Adobe building provides a long chronicle of the successful use of natural plaster systems, with a shorter, more recent chapter detailing mostly unsuccessful changes to that system, particularly the addition of cement. One thing adobe does exceptionally well is to graphically demonstrate its incompatibility with cement. We saw countless examples of the destructive effect cement has on earthen buildings by trapping and wicking moisture: from concrete sidewalks concentrating rising damp, to cement plastered walls that showed no sign of the decay within until they collapsed due to trapped moisture. We saw documentation of an adobe house whose walls began to liquefy and compress after a concrete floor was added. The most telling example was where the base of a wall had begun to erode from improper moisture management and cement was added to fix it, which just wicked the water higher and transfered the damage further up the wall. We feel these examples could be useful to the straw bale builder in demonstrating the superior moisture management qualities (and therefore superior long-term performance) of natural plasters, and to continue to help wean our branch of contemporary building off of high-embodied energy cement-based plasters, which are no better for straw bale walls than they are for adobe.

Clay and lime are abundant and they work: clay transpires, allowing water vapor to pass through it, but swells and seals when wetted with liquid water; lime is not as water-resistant (it does wick water) but provides superior erosion resistance without sacrificing vapor-permeability. But natural plasters require regular maintenance: clay plaster erodes over time and lime plaster develops hairline cracks. The repair is not arduous if done regularly (a skim coat of clay plaster or a coat of whitewash every few years, depending on the climate and exposure) but this seems “labor intensive” in our current culture. Perhaps this can help explain why natural plasters have lost favor over the last hundred years: we are no longer willing to do the labor to maintain them. It seems as though our culture has lost touch with the concept of actively participating in our built environment. We have come to expect our buildings to be permanent and unchanging. For some reason, we have come to believe that completed buildings should not require labor.

Perhaps it is because much of the 20th century was spent trying to free us from labor. The Modernist architect/philosophers envisioned George Jetson-esque building that would perform every chore we needed done: active buildings for passive inhabitants. Vast amounts of energy and resource were spent on buildings that were supposed to heat, cool, regulate, and even clean themselves. Real advance were made in many areas of building but the narrative of the laborless building became larger than the reality, as seen in many modern buildings that provide only the illusion of perfection and permanence and do so at great environmental cost.

Our buildings became “machines for living.” As passive inhabitants ‘liberated from labor,’ we had just one narrow role left to play: the consumer. It seems even our own shelter became an abstract commodity to be consumed, built by others and seemingly too complicated to build or fix ourselves.

The 20th century seemed to view labor as a problem to be conquered by technology and the application of unlimited resources. Is it so surprising then, that as we begin to understand the limits of our resources and seek to reduce the amount of resources applied, we find we need to reintroduce labor? As the energy for these “machines for living” starts to run out, it is interesting to note that human energy is renewable energy.

The newly restored Pitiquito Mission is an active church, used by the local community. This community involvement facilitates the upkeep of the church, particularly the annual whitewashing. Other missions that do not have active communities rely on preservationists to maintain the building. This leads me to what we least anticipated about this conference: how relevant the general philosophical discussion of the preservation of historical earthen structures is to straw bale and larger sustainable building movement. Although some of the conversation did focus on the challenges specific to the public sector (funding, mandates, and mission statements), the overriding themes were very relevant to the sustainable building dialogue.

What emerged was a fascinating discussion of where we have been as a culture and where we are headed, as expressed by our buildings. Building, once a personal and community endeavor, has been transformed over the last century due to cheap and abundant fuel. This seemingly unlimited fuel made the convenience of “anything anywhere” architecture possible. Many local, low-fuel but labor-intensive methods of building were abandoned. The once-intimate scale of choosing a building style and materials radically expanded and became global in scope, seemingly out of the hands of the community and the individual (into the realm of technology and the specialist). Now, as we start to understand the consequences of using so much energy and begin to run out of cheap and plentiful fuel, maybe the scale can shrink, become local again, and get individuals and communities involved again. These historic buildings we saw are living examples, and stand as signposts for us to follow as we negotiate these changes.

Jim Garrison, the Arizona State Historic Preservation Officer, being careful to point out that he was not the first to make the point, reminded the group that the greenest buildings are the ones that are already built. I had heard this idea expressed in relation to the virtues of remodeling an existing building versus building a new one, but it has an extra breadth and depth when considered in the context of historic preservation. Not only are they the greenest buildings because they already exist and the resources needed to build them have already been used, but also because many historic buildings can provide us with examples of the most appropriate technologies and building systems for their specific environment.

By preserving the knowledge to build and maintain adobe buildings, we keep another tool at our disposal, a wider range of options, and a greater bank of knowledge to draw from. If we approach future building with a philosophy that no technology, old or new, is out of bounds as we consider the most appropriate ways to build in our changing world, and remember to ask the questions “Where? What is it like there? What are the local resources and skills? What technologies are most appropriate in this environment?” we will find a new direction. I hope it’s one that puts people back into the equation and views labor not as a problem but as part of the solution.

As straw bale advocates, we thank our new friends in adobe conservation for broadening our horizons and adding to the critical dialogue of why and how we build. Straw bale building, as a relatively new system of building, has evolved quickly and is uniquely poised to integrate the old with the new. We are in a unique position to appropriate the appropriate.

For more information, contact Rebecca Tasker at rebecca@simpleconstruct.net. Also see:

Mission Initiative www.missions.arizona.edu

National Park Service www.nps.gov

INAH www.inah.gob.mx/

University of Arizona Preservation Studies www.cala.arizona.edu/preservation/

Tumacácori National Historical Park www.nps.gov/tuma

San Xavier Del Bac www.sanxaviermission.org/

Caborca Mission www.vivacaborca.com/

Pitiquito Mission www.nps.gov/archive/tuma/Pitiquito.html

BARC www.parks.ca.gov/DEFAULT.ASP?page_id=24175 & www.simpleconstruct.net

straw bale building www.strawbuilding.org & www.simpleconstruct.net

all photo credits: Rebecca Tasker, 2008 except the Minaret at Jam from www.greatarchaeology.com